https://kathmandupost.com/movie-review/2024/05/22/mansarra-the-story-of-vulnerability

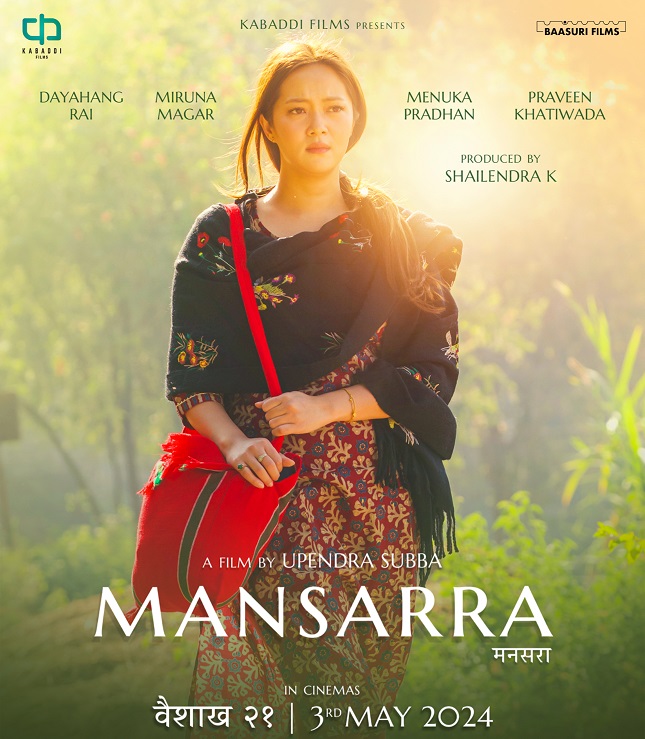

The film conveys the importance of being gender-sensitive, embracing one’s culture, accepting infertility without stigma, and patiently awaiting true love.

Miruna Magar and Prabin Khatiwada in a scene from the movie. Screengrab via YouTube

225

Hisila Yami

Published at : May 22, 2024

Updated at : May 22, 2024 07:55

The beauty of the film ‘Mansarra’ is that it is simple yet holistic and based on ground reality. It subtly addresses migration issues, cultural and national assimilation, intergenerational conflicts and family vulnerabilities.

By addressing these many issues, it shows how they affect human relationships’ sensitivities and responsibilities.

The movie begins with a vibrant Limbu woman named Manrani falling in love with a man named Manahang, who is preparing to leave for foreign employment. Pregnant with a child that is not yet socially or legally recognised, she decides to move to Kathmandu to escape her identity as an unwanted, unrecognised, expectant mother.

She ends up in a tinned shed on the outskirts of Kathmandu Valley, starting a precarious, complex, and uncertain life as the head of a single-parent family with her son, Tancho. This role is sensitively yet boldly portrayed by Miruna Magar.

Meanwhile, an educated but unemployed Brahmin youth named Dadhiram arrives in Kathmandu, haunted by his infertility, which he refuses to acknowledge. After leaving his first wife, Laxmi, who persistently urged him to see a doctor about their inability to have children, he brings his second wife, Nanimaya, to live in the same compound where Manrani resides with her pigsty.

He starts a business supplying milk from the cowshed. Under pressure from his second wife, he agrees to visit a doctor to address their issues, only to discover the truth about his infertility. This revelation leads to increasing tension between them as he struggles to accept his infertility. Prabin Khatiwada skillfully portrays this role of vulnerability.

Meanwhile, Dadhiram starts showing interest in Manrani. He attempts to win her over by helping with her difficult tasks and caring for her child in her father’s absence. This growing bond eventually leads to the end of his relationship with his second wife. The movie’s climax unfolds as the relationship between Dadhiram and Manrani intensifies, with Manrani feeling bitter over her lover, Manahang, not returning.

Dadhiram tries to win Manrani over by aping Limbu culture, even eating pork, only to be rebuked by her with the remark, “Do you think eating pork will buy love?”

It’s interesting to note that while Dadhiram is blamed and shamed by his first and second wives with the derogatory term namard (impotent), he showers love on Tancho, who craves fatherly affection in the absence of his missing father. Nenahang Rai aptly plays the role of the child artist. This complex relationship and the confusion it brings to Manrani are beautifully portrayed.

Failing to get Manrani’s attention and having lost his second wife, Dadhiram starts drinking heavily. When he becomes a burden to her, she poignantly remarks, “I thought I had a good, helpful neighbour—a decent, educated Brahmin—but Baje, you too turned out to be like any other man who is diseased.”

Meanwhile, Manahang returns from abroad and begins searching for Manrani in Kathmandu.

Dadhiram receives a call informing him that his father has been hospitalised. He is rejected by his ailing father for his past actions. This leads to a confrontation where Dadhiram expresses his grievances against his father, saying, “What am I to do if I am infertile? Will being infertile wipe out my name and my cast?”

The scene is so compelling that he, who has been seen as a disillusioned wife basher and cheater so far, becomes a symbol of sympathy, empathy and social inquiry.

It is equally interesting to see how the father and son come to terms with reality. The movie playfully uses the smell of pig and cow dung and the purity of khoa as symbols of different cultures and tastes.

Overall, the movie effectively portrays how women, in general, are resilient, responsible and true to their hearts even in adversity, while men, in general, may falter when faced with uncertainties. It also highlights the societal double standard where wives are blamed for infertility while infertile husbands often walk away, sometimes even being unfaithful towards their wives.

It’s worth watching how, in the end, everyone learns valuable lessons in this film—to be gender-sensitive, embrace Nepal’s rich culture, accept infertility without stigma, and patiently await true love. The film’s conclusion is a win-win, almost believable yet hopeful.

Apparently, Mansarra, in the Khas language, is a type of paddy crop produced in Jhapa. When planted alone, it does not produce rice; it produces husk. But when mixed with other varieties of rice seeds, it yields different varieties of rice. This symbolism is reflected in the film, which accurately portrays the richness of Nepal’s diversity of nationalities.

It’s remarkable that the film has such a minimal budget, and yet portrays a wide variety of important issues. Upendra Subba, the director and scriptwriter, deserves praise for these achievements.

Mansarra

Director: Upendra Subba

Cast: Dayahang Rai, Miruna Magar, Prabin Khatiwada

Year: 2024

Language: Nepali

Run-time: 2 hours 12 mins

Hisila Yami

Yami is a former minister.