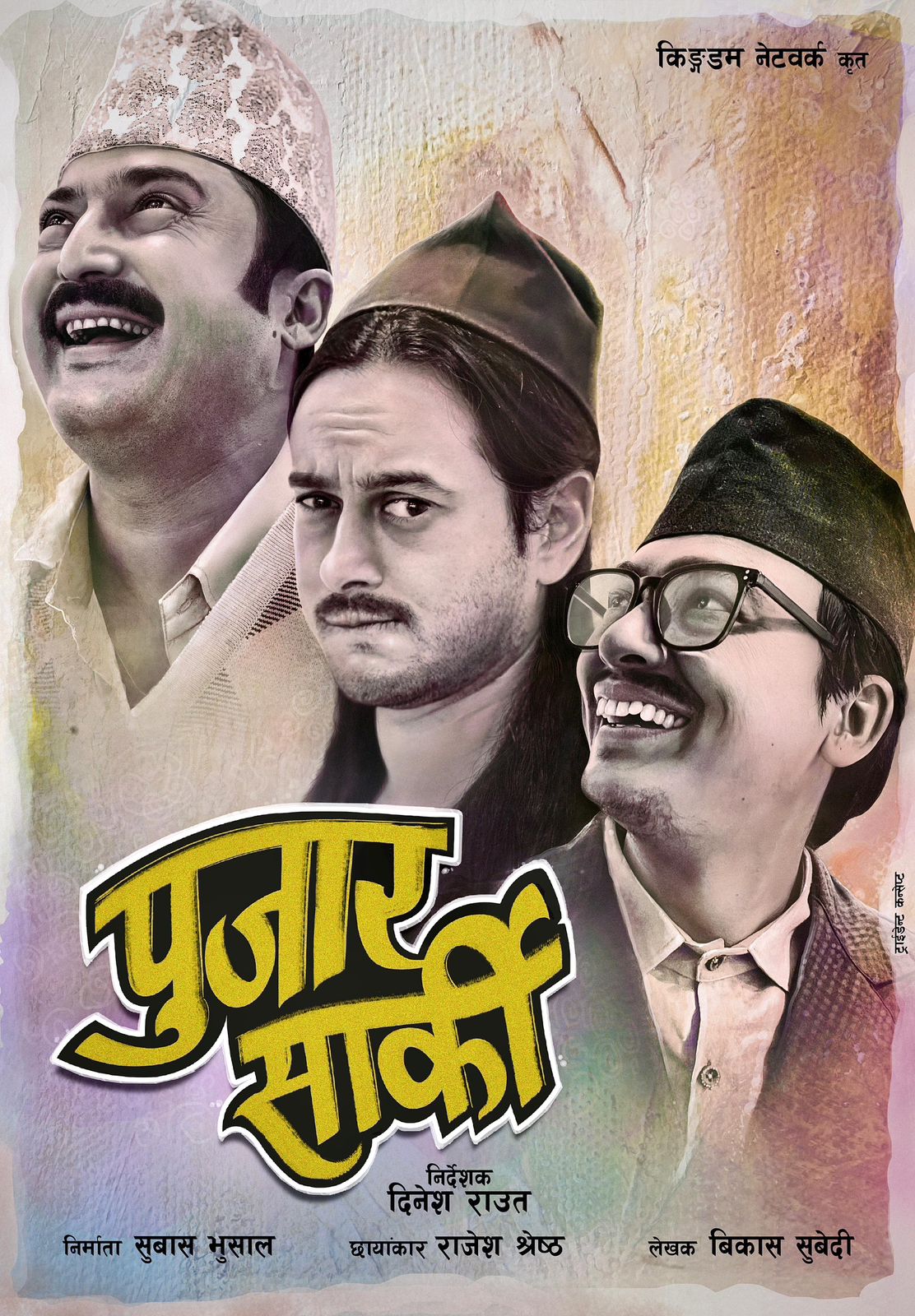

‘Pujar Sarki’ explores caste discrimination through a moving narrative of love and political turmoil.

Pradeep Khadka (left) and Paul Shah in a scene from the movie. Screengrab via YouTube

Hisila Yami

Published at : June 12, 2024

Updated at : June 14, 2024 14:22

‘Pujar Sarki’ shows how love becomes a victim because of the discrimination that exists in the caste system. The film poignantly depicts the yearning between two individuals, a love that tragically succumbs to brutal violence. The cruelty portrayed in the movie is both gruesome and meticulously calculated.

The film opens with a declaration that the People’s Movement has begun and concludes with a political activist’s statement, ‘Jatiya bibhedh murdabad’. Both these explicit and implicit political messages are artistically conveyed to an audience that is becoming more politically disillusioned and apathetic.

The movie swiftly transitions to a love scene between a young Damai boy, Maite, portrayed by Pradeep Khadka, and a young Magar girl, Gaumaya, played by Parikshya Limbu. Just as Gaumaya’s father confronts Maite about their relationship, the scene shifts to a Brahmin priest, Pujar (Aryan Sigdel), seen flirting with Maiya, a Kami girl and temple cleaner, played by Anjana Baraili.

This dramatic revelation pushes Maite to defend his relationship with Gaumaya. At this juncture, Meghraj Chhetri, a political agent of the communist party, played by Paul Shah, offers to officiate Maite’s marriage if he agrees to join the party. Interestingly, Pujar also tries to persuade Maite to convert to Brahmanism, promising to keep his relationship with the Kami girl a secret.

It’s noteworthy that while Pujar successfully marries Maiya, defying his community, Maite, being a Dalit boy, faces greater challenges in consummating his relationship with a non-Dalit girl.

He is caught trying to become a Brahmin by reading the Vedas, and his father warns him, “Do not read, you will be killed.” This situation is reminiscent of Eklavya in the Mahabharata. On the other hand, his attempt to join the Communist Party fails to yield any benefits because the party ultimately sides with the oppressor.

It is interesting to see social reform clashing with political revolution in addressing Dalit oppression. This is where director Dinesh Raut and writer Bikash Subedi deserve credit for cleverly engaging the audience with a love story while subtly conveying important social and political messages.

Similarly, at the societal level, it’s intriguing to observe how the body of a non-Dalit woman is seen as a vessel of cultural “purity” when she marries a Dalit man. Yet, the so-called “impurity” of a Dalit woman’s body is overlooked when a Brahmin decides to marry her. This demonstrates how patriarchal power wavers depending on whether one is Dalit or non-Dalit.

A Brahmin Pujar daring to change his surname to Sarki after marrying a Sarki is indeed revolutionary. However, a Dalit man being chased to death for daring to marry a non-Dalit woman is equally a counter-revolutionary act.

What is most revealing is that Pujar was punished for supporting this ‘unholy’ alliance, leading to both being pelted to death by a frenzied mob incited by non-Dalit perpetrators.

Similarly, when Meghraj states that the political party can address this deep-rooted Dalit oppression, the question arises: Which political party—a power-mongering party or a transformative party?

The film concludes with Meghraj embracing transformative politics, taking to the streets to empower Dalits. Despite being whisked away in a police van, he shouts, “Down with caste discrimination!”

The message is clear: the movement against Dalit discrimination will continue, both at the societal and political levels.

The background of the people’s movement and revolt (almost a People’s War) has been cleverly intertwined with social movements to highlight the compromises and contradictions between Dalits and non-Dalits, between power-hungry political parties and transformative politics. In this film, cultural violence is stark, while political violence is loud. However, the absence of gender violence is noteworthy.

Technically, the film is very engaging, with songs and dances interspersed with the narrative. Dalits are portrayed using instruments such as a sewing machine, cobbler tools, and a drum in the temple in their daily lives. Throughout, the film successfully captivates the audience with pleasant surprises and gripping scenes.

The director cleverly used commercial urban youth actors such as Khadka, Sigdel, and Shah to attract the youth audience. What surprised me the most was how they transformed themselves into mature, responsible actors in rural settings.

He has also aptly used Baraili, a Dalit actress, to portray Maiya. She has acted with empathy and ownership. Similarly, Limbu, as a Magar girl, is able to bring innocence combined with outright frankness, embodying the character of an indigenous person.

He has been particularly successful in portraying the complex character of Maite, the abandoned child with an identity crisis whose foster Dalit parents instilled in him a strong Dalit identity, causing him to be not only angry but often eccentric. Khadka deserves credit for evoking empathy as well as bursts of laughter from the audience through his eccentric tantrums.

Sigdel, in the role of Pujar, successfully conveyed the strong message that Dalit liberation is incomplete without the support of progressive Brahmins. Similarly, Shah, as Meghraj, serves as a good example of a transformative political activist. As an agent of progressive change, he threatens traditional power-mongering political leaders. Their days are numbered.

Hisila Yami

Yami is a former minister.